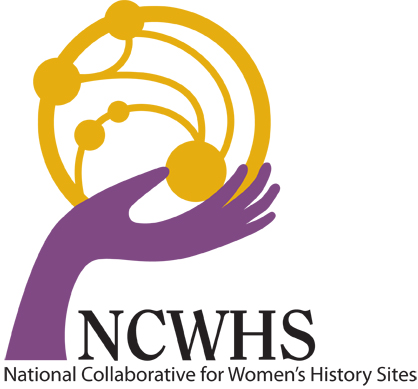

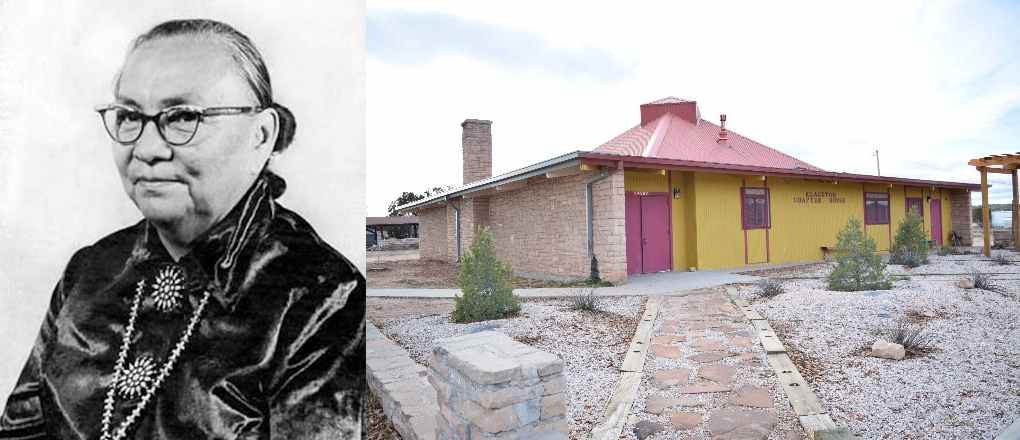

Annie Dodge Wauneka, Navajo. Courtesy of the National Archives. Klagetoh (Leegito) Chapter House. Courtesy of R. Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons

National Historic Landmark Nomination for Klagetoh (Leegito) Chapter House Recognizes Navajo Leader Annie Dodge Wauneka

Born in the traditional hogan of her mother on the Navajo reservation in 1910, Annie Dodge Wauneka rose from the humblest beginnings to the heights of power and prestige through her lifetime of tireless efforts to improve the health and welfare of her people, preserve their culture and identity, and help them navigate their changing world. In 2015 the National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites (NCWHS) and the National Park Service (NPS) embarked on a project to recognize the national significance of Wauneka, one of the most distinguished and influential twentieth-century Native American leaders. NCWHS commissioned the preparation of a National Historic Landmark (NHL) nomination honoring Wauneka under the NPS Women’s History Initiative. Fewer than 2,600 historic properties in the United States have received NHL designation.

Wauneka herded sheep on her father’s ranch as a girl, endured separation from her family and traditional lifestyle at government boarding schools, and later experienced traumas of the livestock reduction era on Navajo lands. As a daughter of the celebrated head chief and the first Tribal Chairman, Henry Chee Dodge, she absorbed much about Navajo culture and developed an ethos of public service, later observing, “From my childhood, I have been made aware of the problems of my tribe and I have wanted to help make our people aware of them.”

Wauneka’s formal political career began in the 1940s as a member of the Klagetoh Chapter of the Navajo nation, one of the tribe’s grassroots community decision-making units of government located in rural northeast Arizona. Despite the demands of raising a large family and operating a livestock ranch, she became one of a small number of women to run for a seat on the Tribal Council during the early post-World War II period and the second to be elected. Serving from 1951 until 1979, she proved to be a most diligent and effective member whose work extended throughout the Navajo Nation and beyond. She displayed remarkable fluency in both English and Navajo, which supported her abilities as a talented interpreter for both cultures and a spokesperson for her own. With her strong voice, vast influence, and tireless energy, she ensured her tribe preserved what historian Peter Iverson describes as “a way of life, flexible and changing, which is identifiably Navajo.”

Healthcare Advocate. Wauneka’s career resulted in a wide range of important accomplishments in fields including education, agriculture, Indian rights, and empowerment of women. Especially significant was her lifelong focus on health care, a remarkable effort which substantially improved the lives of Navajo and other Native American people, contributed to the character of American community medicine, and changed federal agency level healthcare. She became the foremost healthcare advocate for Navajos in 1953, when the Tribal Council drafted her to lead their fight against a devastating tuberculosis epidemic on the reservation. As the only woman on the council, her colleagues believed she was the logical person for undertaking the enormous task. Early in the process, Wauneka identified the need for cross-cultural coordination of the care offered by medicine men, government physicians, and a group of volunteer doctors who offered their services and an effective new drug. She also developed a method of educating Navajo patients that respected their traditional beliefs and customs, clearly answered their questions, and alleviated their distrust of western medicine. Indian Health Service (IHS) physician Carl Hammerschlag deemed Wauneka “a boundary person, a bridge person, one of those rare individuals who can stand between different cultures and help them bridge their differences.”

When Wauneka began her work among the approximately 69,000 Navajo people, many lived scattered in isolated rural areas lacking utilities and improved roads. She realized, “I had my work cut out.” After spending months studying the disease and its treatment, Wauneka drove alone across the reservation from hogan to hogan, sleeping wherever she found herself at night and continuing with her work each day. She explained such concepts as germs, tuberculosis, x-rays, drugs, hospitals, and convalescence to people in their homes, where she also observed their living conditions. This field research led her to develop other programs designed to improve her people’s health in areas such as housing, sanitation, water quality, nutrition, pregnancy and infant care, ear and eye conditions, vaccinations, and alcoholism. She became an innovator of methods to instruct people about achieving better health, including presenting a weekly radio program, producing films narrated in Navajo to use as teaching tools, compiling a Navajo-English dictionary of medical terms, and organizing baby contests as opportunities for medical screening. “She was the guardian of her people. To save them she had to convince them they needed modern medicine, a nearly impossible task in the mid-20th century,” the Arizona Republic assessed. Former Navajo Nation President Peterson Zah concludes that “she literally saved thousands of lives.”

As her efforts brought positive results in the fight against tuberculosis and other problems on the reservation, Wauneka gained national prominence and served in numerous advisory roles, secured increased funding for Indian health initiatives, and achieved recognition as a leading expert in the field of Native American healthcare. She received dozens of awards for her work, most notably a 1963 Presidential Medal of Freedom bestowed by President John F. Kennedy and presented by President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Peterson Zah judges her a person of overarching significance, stating: “To me, she’s almost like Gandhi. I think she did more for her people than any other Navajo, man or woman.” The Navajo Nation awarded one of its highest honors to her in April 1984, designating Wauneka “Our Legendary Mother of the Navajo Nation” for her humanitarian work for the welfare of her people and years of service on the Tribal Council. Professor Iverson regards Wauneka as “a woman of truly legendary proportions.”

Governmental Leader. Annie Dodge Wauneka was a groundbreaking government leader at a time when American women rarely held national political office. In 1951, the US Congress included only one woman senator and ten representatives. Few nationally elected women officeholders of the time compiled a record of political longevity or achievement approaching that of Wauneka. She made dozens of trips to Washington, D.C., where she was a respected representative of Native American interests and conferred with presidents, members of Congress, and the heads of government agencies. Residents of the Navajo Nation continue to regard her as a role model and a courageous and caring politician, who encouraged, mentored, and inspired both men and women to seek government office. Within Navajo politics no other female office holder is comparable to Wauneka. Professor Jennifer Nez Denetdale calls Wauneka “the most prominent woman council delegate.”

When Wauneka entered the Navajo Tribal Council it faced enormous challenges, including high rates of poverty, unemployment, and disease, but also newfound opportunities for progress resulting from abundant natural resources, an understanding of the limits of federal programs, and a growing movement toward self-determination. She shaped the tribe’s response to critical issues and became an articulate and outspoken leader, whose opinions were respected and influential. Former Navajo President Albert Hale estimates Wauneka to be “one of the great Navajo leaders,” who led the transition of the Navajo Nation from “farming and sheepherding to the modern mixed economy of today.” Wauneka’s long tenure, tenacious championing of issues important to Native Americans, service on national advisory commissions, and numerous awards and recognitions guaranteed her prominence throughout the United States.

The Klagetoh Chapter House. The 1963 Klagetoh (Leegito) Chapter House, standing within the Navajo Nation in Arizona, is the resource best representing the public life and nationally significant activities of Annie Dodge Wauneka. NPS staff and the nomination preparers conferred with Wauneka’s family members, including her daughter Irma Wauneka Bluehouse, to identify the building most closely associated with her life of service and appropriate for designation within the tenets of Navajo culture. The chapter house, whose members support the designation effort, reflects the Diné preference for recognition of a community rather than a single individual. The chapter house is where Wauneka developed her political skills and is associated with the community she represented and served for her entire career.

The distinctive building, located forty-four miles west of Gallup, New Mexico, served as a place for Wauneka’s constituency service activities. There, she listened to the concerns of her people, advised them about Navajo Tribal Council decisions and programs, and reported the results of her travels and meetings with government leaders. Historical records document that she played a dominant role in securing the necessary funding for the building’s construction, determining its design and materials, and guiding its programs. The chapter house retains a high degree of physical integrity and conveys a Navajo architectural aesthetic through its use of native materials, stone masonry, hogan-inspired features, and interior simplicity, all of which resulted from Wauneka’s influence. She personally led the chapter members in their rejection of a money-saving, streamlined modern building first proposed by the tribal government, demanding a chapter house whose appearance was informed by historic Navajo architecture.

Already in declining health, Annie Dodge Wauneka made her final trip to Washington to receive an Indian Achievement Award in 1992. A companion traveling with her reported, “As we entered that banquet hall, she just came alive…. That was her turf, her territory.” When she received an honorary doctorate from the University of Arizona in 1996 her grandson Milton Bluehouse, Jr. accepted the award on her behalf and observed: “I didn’t know she was famous until about my senior year in high school. Before that, I figured she was just my grandmother. I thought, grandmothers do these things. They jump in their trucks and go everywhere.” Annie Dodge Wauneka passed away at the age of eighty-seven in 1997. In 2000 she was posthumously inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. In his 2006 proclamation for Women’s History Month President George W. Bush focused on her, stating that “Presidential Medal of Freedom winner Anne Wauneka worked to educate her native Navajo community about preventing and treating disease.” In a statement celebrating all women on International Women’s Day in 2017, Navajo Nation President Russell Begaye paid tribute to Wauneka for her lifetime of leadership and work dedicated to improving the health and welfare of the Navajo people. Her life was called an inspiration to young people and she was extolled for continuing “to be the driving force for change on the nation.”