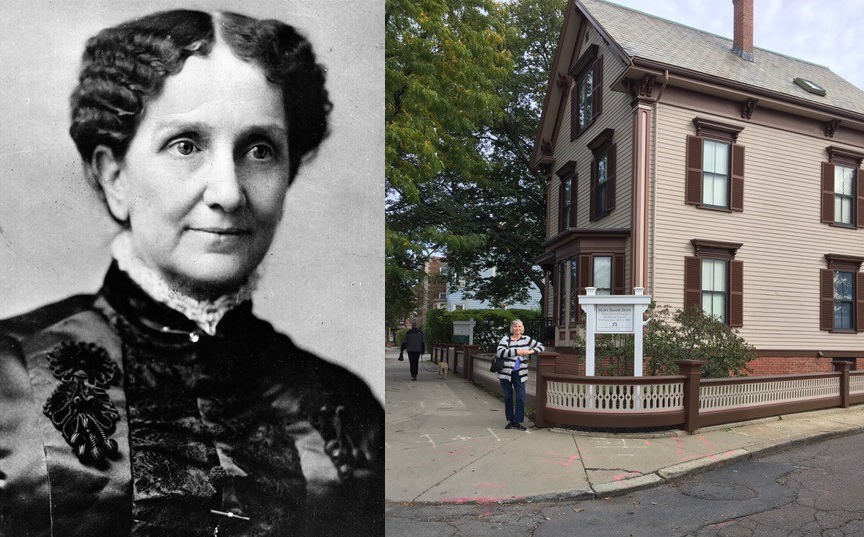

Mary Baker Eddy. Courtesy Library of Congress. Mary Baker Eddy House, Lynn, MA. Courtesy of Judy Wellman.

Mary Baker Eddy Home, 8 Broad Street, Lynn, Massachusetts

Born in July 16, 1821, Mary was the youngest of six children in the Baker family. She spent much of her youth chronically ill. She received an education from supportive men in her life, despite her illness. Her religious training reflected New England Protestantism of the early 19th century, although she disagreed with the doctrine of predestination. During her early education she became interested in writing.

As a young adult, Eddy faced the loss of a number of significant people—her brother, her first husband, her mother, and a new fiancé. Still in frail health, Eddy tried to support herself but writing and teaching could not sustain her. She married again, but this choice proved difficult as her husband deserted her for months at a time. She finally received a divorce on the grounds of adultery.

These experiences, her frailty, and her questions about predestination led her to research the role of the mind in curing physical illness. She tried a variety of alternative medical practices, which had minimal effect for a limited time. Then, she had what she described as an epiphany: that the source of physical ills could be resolved with faith and mental focus. For the next decade, 1866 to 1875, she developed and applied the scientific method of using one’s mind through the “ever-operative divine Principle” by which she meant God.

In 1875, she purchased a house in Lynn MA, started lecturing, and completed her seminal book Science and Health. In it, she outlined a healing method she hoped would reform religious practice in the Christian church through a return to “primitive Christianity,” as she came to call it. The book would undergo multiple revisions and printings, become one of the most influential books on spirituality ever written by an American, and help launch a new denomination. Eddy’s initial hope of reforming existing religious beliefs gave way after multiple rejections by the public. Nevertheless, her own followers grew and together they formed a new Church of Christ (Scientist).

The Christian Science movement grew rapidly through the 1880s. Eddy held classes in Boston and in Chicago where she travelled to teach those who expressed an interest in Christian Science in the Midwest and beyond. She established and edited a monthly magazine called The Christian Science Journal; founded the National Christian Scientist Association; and added a Normal class at her college to educate trained teachers of Christian Science to spread the religion as they convened classes of their own across the country.

As public interest in Christian Science grew, so did public criticism – especially from the twin male bastions of the clergy and the medical establishment. Both felt threatened by this outlier’s incursion into their territory, and both resented the defections from their ranks. The affront was compounded by the fact that Eddy was a woman.

While feminist issues were never the main thrust of Eddy’s work, her life offers a prime example of a woman rejecting conventional gender roles and creating a space for herself outside the social strictures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Her movement recognized a dual-gendered Deity and valued the contributions of both sexes equally. From the beginning, women played an integral part in the Christian Science movement, as healers, teachers, lecturers, editors, and church officials. In founding and leading a successful movement of national and eventually international scope, her life mirrored and exemplified the social currents of the late 19th century, as women expanded their traditional roles in society.

The house at 8 Broad Street in Lynn, MA proved the best location to recognize Eddy’s contributions to the United States. She purchased this as her first home. She completed and published her most important theological statement, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, here. In this house, she taught and preached formally leading to her establishment of a church and college. She established the foundation for her church organization that launched a trajectory that would take her to the national stage and beyond. The Longyear Museum restored the house following its purchase in 2007.

The National Collaborative for Women’s History Sites, at the request of National Park Service, Northeast Division, worked with the Longyear Museum to propose Eddy’s home as a National Historic Landmark in 2016. The Museum completed and submitted the proposal to the NPS in December 2018.